Up to something

Up to somethingThe Guide, July 2004

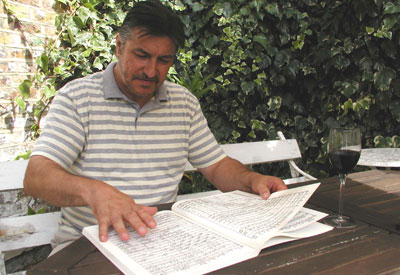

YOU WOULD THINK a conductor would be mildly eccentric, passionate and committed and that's what I'm expecting Robert Trory to be like. But instead I get salmon, red wine and his mum, who is up for the day from, "Hoveactually," which she tells me is next to Brighton.

She is nearing 80 and has her leg up on a stool. She does the classic mum-thing of informing on her son whenever he is out of the room: "Oh yes, he's never been able to sit still, always up to something ever since he was tiny."

That "up to something" is now bringing the Royal Philharmonic orchestra to Catford for a season. Robert is conducting it himself. This is quite a coup. The Royal Philharmonic Orchestra is a world-class orchestra made up of some of the country's finest musicians. Internationally they have played for Pope John Paul ll at the Vatican, the President of China in Tiananmen Square and at the tenth anniversary celebrations of Kazakhstan's independence. So why are they coming to Catford?

This is in effect, "an inner city residency" says Robert. Twenty years ago London orchestras gave concerts in provincial towns regularly. But now local authorities have no money to subsidise such high culture and no orchestra can afford to put on such a concert itself. Lewisham, argues Robert, is like a provincial town - it is the same size as Leicester, with a population of 350,000 - and so really he is updating an old idea of bringing the culture to the community.

Over the salmon (he invited me to lunch in his home in Nunhead) he makes circles with his fork. "It's the donut effect," he says. Audiences in central London are made up of people from the suburbs and the centre he says, residents from the outer boroughs (eg Lewisham) don't bother travelling in because transport is so difficult, especially at night when trying to get home.

So Robert, working through Sydenham Music, the organisation he founded in 1998, has revised the idea of provincial tours and asked, "Why do we have to bus people in to the Royal Festival Hall?" Instead, bring the RPO out here, to Lewisham.

And handily, there is Lewisham Council, one of the most culturally aware councils in London (if not the only one), which is not averse to spending money on arts under their Creative Lewisham banner: promote the arts and promote community. Lewisham has supported Sydenham Music for three years and has granted it £50,000.

"I think we're setting up something pretty unique. I don't think any other borough is doing anything like this," says Robert.

The Philharmonics

There are four orchestras in London. The London Symphony Orchestra (LSO) was established in 1901. The London Philharmonic in the early 1930s. The Royal Philharmonic Orchestra was set up in 1946 and the Philharmonia Orchestra also in 1946.

The Royal Philharmonic is the only one not to have a permanent home, although it has just been given a rehearsal space in Cadogan Hall, Chelsea.

Robert has not always been a conductor. Before studying eight years ago in Russia at the St Petersburg Conservatory with the famous Ilya Musin (born in 1903 Musin turned to teaching when Soviet anti-Semitism thwarted his conducting career and was professor at the Conservatory from 1929 until he died in 1999) he was a concert violinist for many years. A fact, he says, "that disappoints some people". He means other musicians, the people he conducts. It is easy to imagine some members of the highly strung world of violinists being quite put out if they knew their conductor had, a decade ago, been one of them.

However, he is a conductor now: "I couldn't sit in an orchestra now," he says. And he is passionate about it. Not only passionate but good too. After his first concert with the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra the music critic Denby Richards wrote, "Tchaikovsky's 1812 Overture became the masterpiece it ought to be".

By dessert, Robert is into his stride. He has impressed upon me how good the acoustics of the Broadway Theatre are, and he has explained the difference between the RPO visiting Catford and the RPO having a residency here: The residency means the orchestra will be involved in community and schools work, as well as performing a series of four concerts between October and April.

And after all the explanations he is finally into what matters: the music. "My great enthusiasm is for music at the end of the day," he says. "When you get a great audience, a great orchestra, there's nothing better."

In the past six years much of his enthusiasm has been directed into Sydenham Music, an organisation which he and his wife Nina Whitehurst, a violinist in the RPO, established in 1998. The first concert they put on was a fundraiser for Sudan and was in the Church of St Bartholomew. Robert says it is his wife, Nina, who is the real reason the concerts were such a success initially. "She just phones musicians up and they say yes". Musicians around London, from all the different orchestras, now look forward to the benefit concerts promoted by Sydenham Music. It is an opportunity, Robert says, to put aside the everyday inter-orchestra politics and just enjoy playing the music.

Boring Beethoven

And it is the music that Robert is here for too. "We do something with the music," he enthuses. In London, "We have very boring has-been [conductors] who have nothing new to say about music and if we are honest, are bored with the music," he says.

"I go to concerts and I sit there bored. They're boring." This is the worst sin in Robert's world, to make music boring.

"How can you be boring with a Beethoven?" He asks disdainfully.

"He had his own word for it - unbuttoned. You can imagine him with his hair flying and his shirt unbuttoned. How can you be boring with Beethoven?"

To illustrate his point he stands and hunts for two cds. Here, he says, listen to this. It is the introduction to Beethoven's ninth symphony and it's true, it is boring. The second cd goes on and slowly, slowly, something happens. The air trembles as notes rise up, slowly, dangerously, threateningly. Robert smiles, "See?" he asks. The second cd is a recording of the Berlin Philharmoniker from 1942, conducted by Wilhelm Furtwängler.

It was recorded from a live radio broadcast in Berlin at the height of Germany's power during World War Two. The conductor, written off as a Nazi sympathiser but who saved the lives of Jewish musicians by employing them in Berlin, is driven and angry; he is performing in front of Berlin high society, throwing it back in their faces: How can there be an Ode to Joy when there is so much horror?

"Music is me," says Robert. "I feel desperately that I've got so much to say about music that I'll be dead before I've finished." This is what it's about - people and their passion, their reaction, the audience and the orchestra creating something extraordinary for an evening, something to remember for the rest of your life.

"I was aware of music when I was three," he says, "I remember hearing it and thinking 'Oh, I understand this, it's a language, I know it.'" And he weaves his fingers in the air above his head as the notes from the past float above him.

0 comments:

Post a Comment